The individual magazines, which I'd saved, were all thrown out when I came back from university one summer, along with my old schoolbooks and a lot of my writings. We didn't have enough space in our house to keep them all, so they had to go. One issues did escape this fate, though: number 23 (a double-month issue apparently necessitated by "production difficulties").

This issue was important for me because it contained a four-page article about a fantasy campaign called Hyboria, set in the world of Conan the Barbarian. For a 14-year-old boy who wanted to make his own worlds, it was very inspirational. I did thereafter spend a summer making such a campaign world myself, which I planned to run when I went to university. I'd figured already that I could use a computer to do the bookkeeping, and had an ambitious idea to write a program that could run the world itself. Thus, when I met Roy Trubshaw and found that he'd just started work on a such a computerised world, I was already up to speed with the concept — even though I'd never played such a world myself. Roy had played ADVENT, also known as Adventure and Colossal Cave, but I hadn't; I'd read a one-page transcript of ADVENT in a zine I subscribed to, Bellicus, but that was the extent of it. Nevertheless, it was clear that what Roy was making, I too wanted to make. The scale was smaller than what I'd planned, but the artistic purpose was the same. My interest in implementing a world myself rapidly declined.

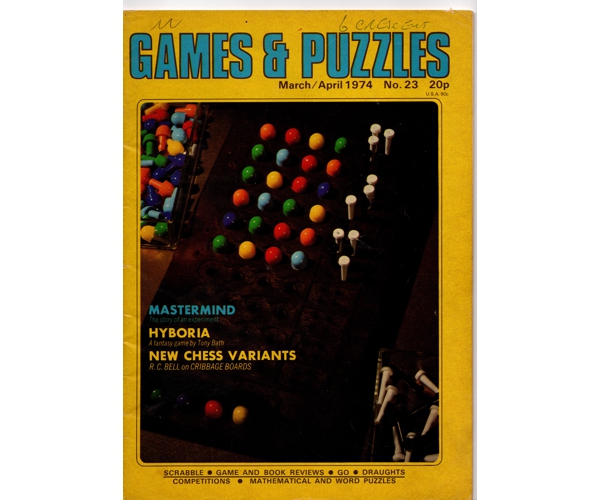

This particular issue of Games and Puzzles cost 20p. My rule of thumb for thinking of old prices in modern terms is that a shilling in my childhood is about a pound today, so 20p would be worth around £4, maybe a bit less. The interior of the magazine is not as well laid-out as modern magazines, probably because automatic typesetting was expensive back in 1974. The advertisements are particularly amateurish at times. This wasn't something we really noticed, though, because the same problems beset most magazines. We were interested in the content, not the layout.

The reason issue 23 wasn't thrown out along with the rest of the collection wasn't because I managed to rescue it from the pile: it was because it was in the box where I'd kept the materials for the world I'd designed. These, I did save from the trip to the incinerator.

Unlike my other game design materials, the ones for my campaign world live in the attic, not on the shelves in my study. They escaped being thrown out once; this increases their chance of escaping a second time.

It hasn't been there for 40 years, but maybe I should put Games and Puzzles issue 23 back in this box, too.