I always thought this was a weird super-injunction. Ages ago I read gossip in the newspapers that Ryan Giggs had had an affair with Imogen Thomas, and then just as the newspapers were reloading there came this news of a "super-injunction by a premiership footballer" and the story was dropped. It wasn't too hard to figure out what had happened.

What I found a little odd, though, was that although the super-injunction forbade newspapers from reporting that details of the story, some of the other things super-injunctions typically forbid didn't appear to apply. For example, reporting the existence of the super-injunction (which is one of the worst things about them, because it means a newspaper can breach one without even being aware it was there to breach) was apparently OK. Also, although newspapers weren't supposed to give pointers as to where to find the details of the case, they were full of references to Twitter. That would seem to be breaking the usual terms of a super-injunction — they might as well have told us his initials. And why was it always Twitter anyway? The details were far easier to find on Wikipedia, which had a whole page about it.

At the moment, the future of super-injunctions is looking untenable. However, they do have some valid uses. Suppose an individual were in real danger of being murdered (as Salman Rushdie was when a fatwa was put out on him). The individual goes into

hiding, gets a new identity from the state, and all is well. Then, a newspaper finds out their new name and gears up to publish it. The individual would want a super-injunction, because publication of their new name could mean their death and because the paperwork for a regular injunction could itself be used to track them down. That sounds fair enough to me, and even if a hundred thousand Twitter users thought otherwise I believe a judge would be doing the right thing to insist that Twitter reveal at least the name of the source of the breach.

In Giggs' case, the injunction was unfair (because it only protected his name, not Thomas's) and based on false arguments about protecting his family (he should have thought of that before having an affair). Unless there's something else we don't know about, this seems to be an injunction that should never have been granted. That doesn't mean they all are, though.

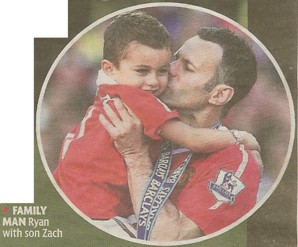

Oh, this was in the Daily Mirror today:

There's sarcasm for you...